Lessons in Popular Culture: Racialization and Disney's Zootopia

During the final weeks of the Popular Culture and Communication course that I teach at the University of Ottawa, we focus our attention on (1) different topics or areas of research that are undertaken in the field of popular culture studies and (2) the effects of popular culture. In particular, we examine how popular culture - and the repeated exposure to certain messages or themes in the media - influences our perceptions of ourselves and of others, and therefore our identities and behaviour.

When building the syllabus for this course, I try to take into account emerging research and trends in the field of popular culture, what’s happening in the world, and what students are interested in learning about. This means that while some topics and readings remain consistent over time, new topics and the study of specific popular culture products (or texts as they’re referred to in the course) are added to the course. This week one of the topics that we look at is race, racialization and the representation of the police (the police state and police violence). This is explored through a reading called “It’s Called a Hustle, Sweetheart”: Black Lives Matter, the Police State, and the Politics of Colonizing Anger in Zootopia” written by Jennifer Sandlin and Nathan Snaza and published in 2018 in the Journal of Popular Culture.

ABOUT ZOOTOPIA

If you haven’t seen Disney’s Zootopia (released on March 4, 2016), I recommend starting by watching these two trailers:

As you can probably tell from the trailers, Zootopia is about an interspecies society featuring two major ‘identity groups’ - predators and prey - who coexist in a city. It also follows the actions of the city’s police. What the trailer doesn’t tell you, is that as the movie progresses, predators begin to turn hostile and aggressive - “savage” - which makes the prey wary of the predators that they run into. Judy Hopps, a rabbit from Bunnyborrow and a new member of the Zootopia police force, is assigned to investigate the disappearance of 14 predators from Zootopia. She befriends and blackmails Nick Wilde, a fox (and predator), into helping her solve the case and the film essentially chronicles the tensions that emerge between predators and prey in the city.

Why study zootopia?

First and foremost, its success! In its opening weekend, Zootopia earned more than 75 million dollars. The film was in theatres for 22 weeks and earned more than 1 million dollars worldwide. This is in addition to domestic (US) and foreign DVD and Blu-Ray sales, as well as other merchandising and spin-off revenue.

Second, the real-world context! The film debuted in the middle of contentious ongoing US (and global) conversations about (1) police violence (2) white supremacy, (3) the police state and (4) the Black Lives Matter movement.

Third, the film has been interpreted as an allegory for the debate surrounding the role of the police and the police state and societal tensions and conversations surrounding race.

What else do we need to know?

The authors on several key concepts which provide the foundation for their analysis of the film:

RACIALIZATION

Racialization is defined as “how race is produced in ways that blur biological/cultural distinction” (1190). This is important because racialization has been said to organize our social, political and economic relations by construing race as a set of socio political processes that separate humanity into full humans, not-quite-humans and nonhumans. In other words, racialization separates society into different ‘types’ of bodies, which affects the privileges or lack thereof that are accorded to those bodies.

Dehumanization

Dehumanization refers to “taking a highly specific version of ‘the human’ and using it as a political standard against which all other versions of the human are judged and found wanting” or missing something (1191). In other words, dehumanization involves doing something that reinforces or allows for thinking of someone (else) as less-than-human. This is important because dehumanization “permits” or “justifies” differential - often harmful - treatment of those that are not like us.

affect

The affect suggests that our emotions have a shared - constructed - social and historical dimension.

how does this relate to walt disney films (and zootopia)

As Willetts notes, Disney films have a history of equating Blackness with servitude, ‘Otherness’, ignorance and buffoonery, as well as including on-screen representations of blackface and the animalization of Blackness.

The Jungle Book (1967)

Featured the character of King Louis, the “jive-talking” orangutan.

The Little Mermaid (1989)

Featured the character of Sebastian, a “Caribbean crustacean and servant to King Triton”

The Incredibles (2004)

Featured the character of Frozone, a one-dimensional Black superhero sidekick to Mr. Incredible

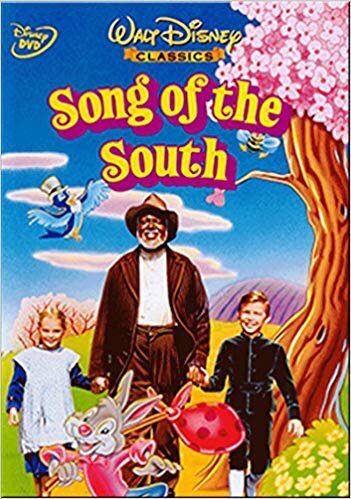

The authors note that while scholars have analyzed countless Disney films and experiences, the two films that have generated the most attention are Song of the South (1946) and The Princess and the Frog (2009).

SONG OF THE SOUTH

Sperb argues that Song of the South depicts plantation life in the late nineteenth century as a white musical utopia when it was, in fact, a time of unimaginable cruelty. He notes that although the film flopped in 1946, it has been re-released several times, corresponding with “significant shifts in White America’s attitudes towards African Americans’ collective struggle for equal rights and opportunities”. This is because it provides audiences with a reassuring image of harmless and content African Americans – back at the plantation, hard at work for their White masters and completely uninterested in equality, let alone freedom

(If you’ve never seen Song of the South, I recommend at least checking out the trailer below)

Song of the South has been highly criticized outside of scholarly literature as well: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/nov/19/song-of-the-south-the-difficult-legacy-of-disneys-most-shocking-movie

the princess and the frog

The Princess and the Frog has been heralded as a progressive Disney film for featuring the first Black princess. The film is set in New Orleans in the 1920s and follows Tiana, a young Black woman, who dreams of opening her own restaurant. She successfully achieves her goal by the end of the movie - and also ends up marrying a prince.

The film has, however, been criticized because Tiana spends most the film as a frog, trying to break a spell and become human again, rather than as a Black woman. In addition, the film is said to “sanitize and romanticize” New Orleans in the 1920s by presenting a ‘colour blind’ version the city where individuals from all cultures, classes and races live and socialize with each other, ignoring that racial segregation was actually at its height in New Orleans in the 1920s

So what?

The authors rely on a body of existing research to support the position that Walt Disney films place an emphasis on positive emotions such happiness, pleasure, excitement, adventure, and escape. Disney uses these positive emotions to drive marketing, experiences, and consumer purchase decisions and, in the context of race, to whitewash or de-emphasize racial tensions, conflicts, and history. This is done by presenting stereotypical and racist depictions of Black characters humour and rewriting historical truths by avoiding and neglecting to past trauma and conflict.

And this brings us to…zootopia!

Click HERE to read about Sandlin and Snaza’s analysis of race and racialization in Zootopia.