The Individual, the Office, and a Bible: A Critical Examination of the President’s and the Presidential “Body”

During the spring semester, I took a graduate seminar in the School of Nursing called “Histoire socioculturelle du corps” (or the Sociocultural History of the Body). I was interested in taking this course for a couple of reasons:

I was teaching an online seminar in the Summer semester and wanted to see what it was like to be a student in an online class;

My dissertation research is related to representations of the body (and I ended up adding a section into my dissertation on teratology and the socio-biological history of the body); and,

I was able to practice reading, writing and communicating orally in an academic context in French.

In addition to the above, I also wrote a paper on “the presidential body” following President Trump’s Bible Photo-op in early June. The paper sits at the intersection of public relations and political communication. Public relations is a little outside of my wheelhouse, but I enjoyed reading for and writing the paper. The mash-up video below provides context for the paper:

INTRODUCTION

Although presidents and the presidential office have always been subject to criticism and reproach, since President Donald Trump ran for office and became the 45th President of the United States, the form and frequency of such criticism has changed. This has only intensified since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent Black Lives Matter' protests.

This critical essay examines how the president's body (as an individual) and the presidential body (as an institution) have been constructed through the use of photography, publicity, and force. To do this, this paper first examines how the physical body of the president has been positioned and represented in photo opportunities (hereinafter referred to as photo-ops) and public relations events to emphasize or minimize certain characteristics. Then, the presidential body (as an institution) is examined to shed light into how it participates in the positioning of the president’s body and how it has been perceived as a result of specific photo-ops and publicity moments.

Finally, as this paper is primarily concerned with seemingly miscalculated photo-ops, the June 1, 2020, photo-op of President Trump holding a Bible in front of Ashburton House, the parish house of St. John's Episcopal Church, during the COVID-19 pandemic and “Black Lives Matters” protests is examined. This paper is among the first to consider the impact of the Bible photo-op beyond its critique, criticism, and possible alienation of American voters on the president, the presidential body, and the body politic.

THE BODY OF THE PRESIDENT

When it comes to presidential leadership, certain characteristics and attributes are valued over others. These include physical characteristics such as strength and health, intellectual characteristics such as decisiveness, competence, and confidence, and moral characteristics such as religion and compassion. These personality traits and qualities are most easily conveyed through images, whether candid or staged, moving or still (German, 2010, p.49), when combined with the use of cultural icons (Cooley, Forrest & Wheeldon, 2006, p.137).

The Athletic President: Patriotism, Health & Youthfulness

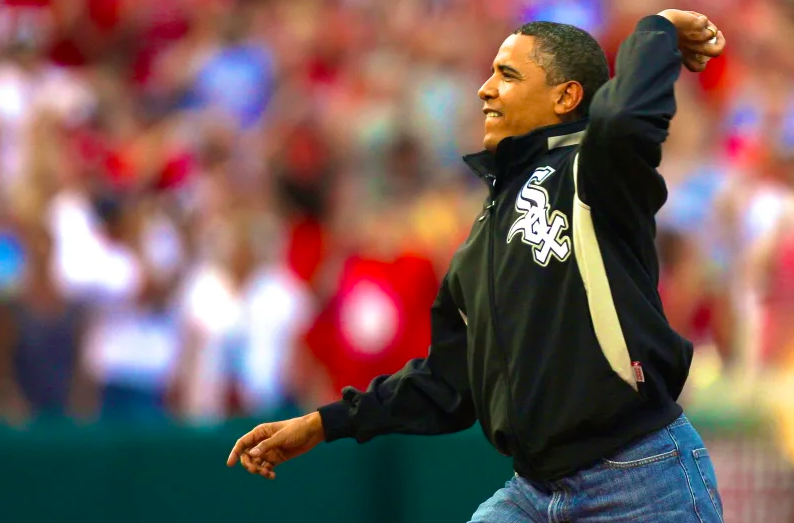

Moore & Dewberry (2012) trace how Presidents from William Howard Taft (1909-1913) to Barack Obama (2009-2017) successfully and unsuccessfully relied on sports and athleticism to evoke ideals of masculinity and, therefore, good leadership. Taft, pictured below along with Obama, started the tradition of throwing the first pitch of the major league baseball season. In addition to masculinity, the appropriation of baseball also speaks to a president’s commitment to “America’s national pastime” (Moore & Dewberry, 2012, p.3) and, by extension, positions the president as a patriot.

Taft throws a baseball in 1910

Obama throws a baseball in 2020

Although the presidential pitch continues to hold significance – President George W. Bush’s pitch in Yankee Stadium less than two months after 9/11 symbolized strength and perseverance (Rymer, 2014) – presidents have also been linked with golf, bowling, jogging, and, most recently, basketball. In addition to masculinity and patriotism, images of presidents participating in sports demonstrate health, vitality, and youthfulness, and are generally perceived favourably by the press and the public except during times of crisis, when they have been interpreted as a distraction and a lack of focus and prioritization (Moore & Dewberry, p. 8). Capitalizing on the popularity of sports also depicts presidents as relatable to the average, everyday citizen.

Military Might: The Strong and Powerful President

Images of the president in uniform or surrounded by military service members and American flags evoke “the spectacle of power” (Chun, 2018, p. 20) by tapping into symbols of authority and strength. However, this has backfired for both presidential candidates and presidents alike. During the 1988 presidential election, to counter criticism about his stance on national security and crime, Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis was filmed riding in a battle tank. The photo-op ‘tanked’ and Dukakis was ridiculed in the media and by his Republican opponent, George H.W. Bush, who later won the election (Kellner, 2002, p.476).

Dukakis, Democratic presidential candidate, in 1988

President George W. Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” press conference in May 2003 similarly received backlash, albeit delayed. After landing on the aircraft carrier the USS Abraham Lincoln, in the co-pilot’s seat of a Navy fighter jet, the President changed out of a jumpsuit and into a dress suit to deliver a speech declaring victory in the Iraq War underneath a banner that read ‘Mission Accomplished’. Originally viewed as an effective photo-op, reminiscent of the popular film Top Gun, it was later seen as a symbol of the many mistakes made by the White House, including those related to the war (Cline, 2013).

George W. Bush arrives on the flight deck in a military suit.

President Bush in front of a "Mission Accomplished" banner

Other ‘Presidential’ Qualities: The Family Man, The Youthful Politico and The Corporate Leader

Strength and masculinity, while linked to good leadership, are not the only qualities that presidents have tried to convey through the media. Lester (2007) calls attention to the use of children in political campaigns and other staged events as a common public relations tool (p.127). Photographs of John F. Kennedy with his children in the Oval Office as well as with Barack Obama and his daughters have been released to the press and on social media. In addition, President Bill Clinton’s relationship difficulties and Hillary Clinton’s continued support of her husband made them both relatable and entertaining (Kellner, 2002, p. 478-481).

Good looks, a nice smile, a full head of hair, and, as mentioned above, athletic prowess also increase the appeal of presidents (Kellner, 2002, p.480). Politicians who are likeable and relatable are often the most likely to succeed. Finally, Ouellette (2016) argues that the success and notoriety of The Apprentice established Trump as an “expert and leader extraordinaire” who uses a “no nonsense approach” to get things done (p.649).

Thus, while common themes exist in the representation of the body of the president, each president must nevertheless maintain a distinct performative identity (Seymour-Ure, 1997, p.32).

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln by Mathew Brady, 1860

The Presidential Body

Traditionally viewed as a revered and trusted institution – even when controversies arise – there are nevertheless countless historical examples where miscalculated photo-ops and public relations events have tarnished the presidential body in addition to the president himself. Erickson (2000) refers to these photo-ops and events as “presidential performance fragments” and argues that they’re strategically designed to manipulate, influence and exert power over others (p.139). These moments often target specific segments of the population with the aim of making the president look good (Alaimo, 2015, p.122) and improve his popularity (Brace & Hinckley, 1993, p.396). Erzikova & Bowen (2019), for example, cite a Hills & Knowlton Strategies blog post that calls attention to how President Trump “court[ed] older white males lacking a college degree, […tapping] into and mobiliz[ing] an electorate that is angry, disenchanted, and feels left behind” (p.5). How does the presidential body employ the president’s body to do this? The answer lies in its exertion of power over access and control.

Exposing the President’s Body: A (New) Media Body

Lundell (2010) notes that “politics is a largely mediated experience” (p.219). While photos have always played an important role in politics – indeed Abraham Lincoln’s photograph, which was reproduced in wood and photographic prints, “made him appear more handsome and less gangly” (PBS, n.d.) – this has never been truer that today as “the visual in its myriad of forms” has become our primary medium of communication (Betts & Bly, 2013, p.61; Foxall, 2013, p.133). In addition to a shift from the textual to the visual (Marland, 2012, p.215), political communication has also become “more performative, more theatrical and more aestheticized” (Holly, 2008, p.317).

It was Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) who ushered in the “modern era of presidential media relations” by providing the media with direct access to him and appointing the first full-time White House press secretary (Frantzich, 2019, 113-114). Kellner (2002) points to the importance of the presidential ‘media spectacle’ for elections and governance. In particular, he draws a distinction between successful and unsuccessful presidencies based on their media coverage and subsequent transition to Hollywood biopics. He characterizes Lyndon Johnson (1963-1969) and Richard Nixon (1969-1974) as cinematically deficient, noting that they came across as “boorish, overbearing, and unpersuasive” and as a villain, respectively (p.470). He also lists John F. Kennedy (1961-1963) and Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) as successful media presidents, noting that they were photogenic and embraced the notion of the president as celebrity.

Reagan’s presidency has been referred to as the “television presidency” (Coyle & Dahmen, 2017, p.339) – and this is not just because he was an actor before being elected. Erickson (2000) states that Reagan “mastered the art of performing presidency” (p.139) and cites Chief of Staff Donald Regan’s (1988) memoir which outlines the detailed planning that went into each event: “Every moment of every appearance was scheduled, every word was scripted, every place where Reagan was expected to stand was chalked with toe marks” (p.139). Under Reagan, the presidential body used advance teams to scout locations, identify red flags and determine the best angles for photos. For example, when he visited Kolmeshole Cemetery in West Germany, an elevated stage and tripods were banned so that photojournalists could not accidentally or intentionally provide a view of the President with an SS grave in the background (Coyle & Dahmen, 2017, p.341).

In addition to embracing the notion of the television and spectacle presidencies, Donald Trump has also created the first “social media presidency”, for he is a president “whose tweets are not bound to working hours, [creating an environment where] responding in minutes, not hours, can make a difference” to those he speaks to and about (Erzikova & Bowen, 2019, p.6)

Power and Control: Access to the President and the Presidential Body

George H.W. Bush at the National Grocers Association convention in 1992.

Access to the president and other members of the presidential body varies from administration to administration. Among other things, it depends on location, timing, context and additional conditions imposed by each administration as well as the value that each administration places on the media (Coyle & Dahmen, 2017, p.337).

In addition, how the presidential body communicates with the public and through whom also varies. Coyle & Dahmen (2017) found that presidents and the presidential body are generally welcoming to photojournalists and the press at the beginning of their time in the Oval Office, granting opportunities for both official pseudo-events and candid photos. This relationship can, however, sour if the photos taken are ill-received or present the president and the presidential body in an unfavourable light – such as when George H.W. Bush visited the 1992 National Grocers Association Convention and was portrayed as ‘amazed’ at the scanning technology used by the cashier and therefore seen as out of touch with the everyday citizen who regularly goes to the grocery store (Coyle & Dahmen, 2017, p.344).

Framing and Staging: From the Pseudo-Event to Ultra-Reality

In addition to controlling physical access to the president and the presidential body, including staff and other representatives, the presidential body attempts to control meaning (Erickson, 2000, p.144). This is achieved through agenda-setting and framing, by carefully selecting what information – visual and verbal – is reported, how it is presented, and what is not (Marland, 2012, p.217; Chun, 2018, p.19). Take for example, the location of a press conference, photo-op or other public appearance. Seymour-Ure (2010) argues that “different places fit different personas” of the presidential body which he identifies as ‘the White House’, ‘the President’, and ‘Insert name of the President here’ – or the ‘President as a normal person’ (p.39). In addition, places and spaces come with a history and symbolic meaning. As such, they must be carefully selected and inspected.

The timing of the photo-ops and their context is also critical to their reception. In their analysis of the response of the presidential body to the 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina crises, ‘t Hart, Tindall and Brown (2009) noted that time pressures may require the White House to act quickly and swiftly. They also called attention to how time pressures impact the characteristics of the president that need to be emphasized during a crisis. While a measured response framed Bush as “caring yet in-control” following the 9/11 attacks, a delayed response coupled with improperly executed photo-ops in the wake of Hurricane Katrina made the president and the presidential body seem “out of touch and disengaged from the disaster” (p.487).

Erickson (2000) outlines the functions of these presidential performance fragments and notes that they “frequently target politically influential and marginalized audiences” (emphasis in original, p.145). He also states that these moments “can divert the public’s attention by commanding headlines and air time that overshadow competing agents, agendas, exigencies, and/or sensitive operations” (emphasis in original, p.147). Erickson (2000) points to two examples of communication diversion: Clinton’s visit to Detroit and release of a new education plan on the day that impeachment proceedings were initiated against him and George H.W. Bush’s efforts to divert attention from the Democratic National Convention and the naming of a presidential candidate (p.147).

President Donald Trump and “The Bible Photo-op”

Donald Trump holding a Bible

Less than a week after the death of George Floyd at the hands of four police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota, amid large demonstrations across the United States protesting racism, inequality and police brutality in the middle of a global pandemic, President Donald Trump posed for photographs holding a Bible in front a damaged church near the White House. To facilitate the photo-op, police used force and tear gas to remove peaceful protestors and clear a path for the President to walk from the White House to St. John's Episcopal Church. Following the photo-op, the White House also released a promotional video on Twitter featuring the President confidently walking with his entourage to and from the church.

The photo-op received both criticism and praise on the Internet: while staff and supporters spoke out in favour of the President; comedians, church officials, journalists, political pundits and everyday citizens ridiculed and condemned the President on social media and in the news. This criticism, while not necessarily undeserved, generally failed to recognize the full impact of the photo-op.

As Erickson (2000) has suggested, presidential performance fragments target politically influential and marginalized audiences. Thus, through the Bible photo-op, Trump was able to appeal to his traditionalist and evangelical base. In addition, the photo-op commanded media headlines, dominated the Twitterverse and, ultimately, diverted attention from other competing events and issues including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests. The photo-op can be characterized as what Diane Rubenstein (2008) refers to as a “non-event”. A non-event, she states, “is not the absence or lack events”, rather it “is that which needs perpetual spin, an endless drip-feed (perfusion) of ‘Breaking News’ bulletins” (emphasis added, p.149). This is precisely what the Bible photo-op did.

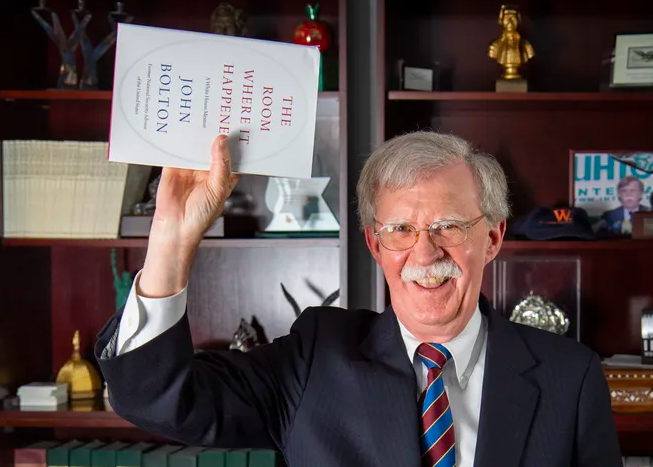

In the days following the photo-op, political and religious leaders loudly and vehemently denounced it; 10 days later, Mark Milley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff released a statement that he regretted taking part in the photo-op; and, on June 21, 2020, Trump’s former national security advisor, John Bolton, posed with his new tell-all book about his time in the Trump Administration, holding it like the President held the Bible during the photo-op.

In addition, the photo-op also “facilitate[d] the inventional management of the presidential personae” (Erickson, 2000, p.142) by positioning the President as a victim bullied by the Leftist media and its supporters, potentially gaining him sympathy from the political right.

Conclusion

This paper examines how the body of presidents has been framed in and received by the press and public, noting that while each president needs to define his identity as a leader – and therefore his presidency – the body of a president is best received when it is understood to be embody specific physical, intellectual, and moral characteristics. The image, whether moving or still, has become the primary tool for conveying this message to a public that rarely if ever will have the opportunity to interact directly with their Head of State. As such, the presidential body attempts to exert control of the president’s body and images of it through carefully choreographed appearances, events and photo-ops.

While these presidential moments, or what Erickson has referred to as ‘presidential performance fragments’, can yield much success if well-timed and expertly orchestrated, they can also give rise to criticism, critique, and even mockery if they are poorly executed. Most recently, Donald Trump’s Bible photo-op in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic and amidst nationwide ‘Black Lives Matter” protests, received local, national and international coverage on every media platform. Although some supporters and religious leaders recognized the nod to traditionalist and religious values, the act was overwhelmingly condemned by celebrities, politicians, religious and military leaders, and everyday citizens from all sides of the political spectrum. And yet, coverage and condemnation of the photo-op dominated the airwaves, displacing news stories about the impact of the pandemic and coverage of the Black Lives Matter protests. Perhaps this moment in time, this presidential performance fragment, was not about religion, power or narcissism – or at least not entirely. Trump (1987) himself has said that “good publicity is preferable to bad, but from a bottom-line perspective, bad publicity is sometimes better than no publicity at all. Controversy, in short, sells” (p.211).

It is without a doubt that this photo-op and the actions leading up to it are controversial. However, it is also possible that this bungled photo-op is not as bungled as it seems. In support of such a conclusion, Erickson (2000) suggests that “a president’s motives are inevitably complex (fiscally, psychologically, politically, militarily) and infrequently self-revealing” (p.152). Only time will tell if President Trump’s display of his political body, his use of the resources of the presidential body and his manipulation of the body politic pay off.

You can find the Reference List for my paper here.