Zombie, zombie, zombie-ie-ie - Lessons from Popular Culture Continued

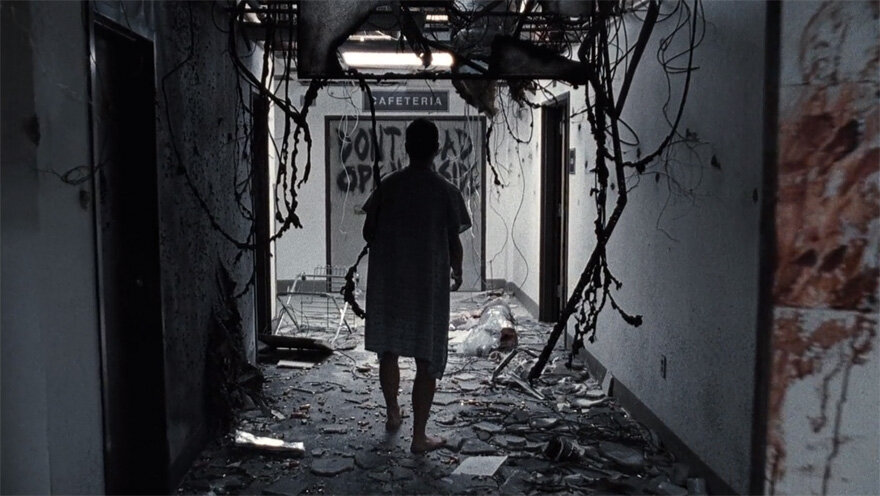

Photo from The Walking Dead (AMC)

Zombies, as mentioned in my last blog post, are everywhere in popular culture and we can learn a lot from studying them and their monstrous siblings - werewolves, vampires, aliens, ghosts and the like.

What do we mean when we use the word ‘monster’ or ‘monstrous’?

Traditionally, when we speak about things that are monstrous, we're referring to someone or something (some act) that is morally reprehensible, or culturally or socially unacceptable. Serial killers, although they’re real-life, living and breathing human beings, are often called 'monsters'.

Monsters and monstrosity have been relied on in the past as a way to define the boundaries of humanity and human nature. They also provide an explanation for what is inexplicable or a justification for what would otherwise be horrendous and unspeakable.

Derived from the Greek word "Teras", which means both abhorrent and attractive, taboo and desire, it's said that monsters simultaneously repel us and draw our gaze. The vampire, for example, has transitioned from something to be feared (like the original Dracula) to an object of seduction or a sympathetic hero.

Angel/Angelus, from Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel

Louis de Pointe du Lac, from Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire

Because monsters sit at this intersection, they articulate our deepest and darkest fears as well as our deepest and darkest desires - they provide a mechanism for exploring behaviour that might otherwise be taboo, unnatural, or in opposition to the status quo. As such, monsters:

Provide a reference for identifying what is normal and natural - and therefore what is not

Allow for the formation and expression of all different kinds of identities - cultural, social, sexual, economic and psychological.

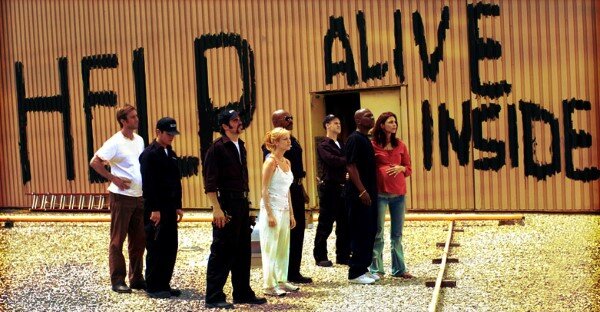

By setting monsters up as abnormal or un-human, it positions us against them and helps to justify the different, dehumanizing and violent treatment of that group. This video from the 2004 remake Dawn of the Dead illustrates that how that treatment plays out in zombie cinema.

It’s “Us vs Them”!

The “Us vs. Them” dichotomy that emerges between zombies and humans in the zombie genre applies to monsters more broadly. It separates characters into two binary and oppositional groups: abnormal vs normal, monster vs human, infected vs uninfected, and so on. This division results in othering, which is the act of dissociating oneself from a group that is different or ‘other’ from us.

So, what happens when language found in monster and zombie tropes spills off-screen into academic and popular culture literature surrounding real-life medical conditions like Alzheimer’s Disease or HIV/AIDS?

Monsters as metaphors

Photo from Ginger Snaps

The comparison of monsters to people living with illness and disease is not far-fetched and has been heavily studied by scholars (in fact, my doctoral research project is about this).

In his 2011 analysis of the Canadian film Ginger Snaps: Unleashed (2004), also known as Ginger Snaps 2, Antonio Sanna argues that the werewolf myth presented in the film acts as a metaphor for incurable illnesses, and points to HIV/AIDS in particular. He identifies several indicators in support of his analysis including that the condition can spread through unprotected sex, is described as a blood disease, and can be treated with curative drugs, but remains incurable. Sanna notes that in Ginger Snaps, unlike in other werewolf myths, one’s transformation to werewolf is final (because the wolf cannot shift back to their human form) and therefore results in one’s human death. Similarly, a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS frequently, eventually, contributes to a person’s physical and social death.

Zombies and Alzheimer’s Disease

Behuniak (2011) sets out to explore what she saw as a troubling trend in both scholarly and popular literature on Alzheimer's Disease which links the disease to zombie-related language. She provides several book titles as an example of this, including Alzheimer's Disease: Coping with a Living Death and The Living Dead: Alzheimer's in America.

She identifies other themes in both academic and non-academic sources that, subtly and not-so-subtly, invoke the zombie metaphor including the destruction of the person and the reanimation of the body, a type of death before death, the funeral that never ends, and the drawn out nature of dying. Behuniak suggests that it can be hard to determine what source or language is actually referring to zombies and what source or language is actually referring to people living with Alzheimer's Disease.

Behuniak (2011) suggests, in the case of Alzheimer's Disease, that "the script is literally lifted from the world of film" (p.73). What is happening, she argues, is that the zombie metaphor is seeping into our understanding of Alzheimer's Disease, such that we've started to recognize zombie-like characteristics and behaviour in people living with the disease, which in turn has implications for how they're treated in society.

To examine this phenomenon, she identified 7 characteristics from George A. Romero's zombie films and then did a search for them in scholarly and popular culture literature on Alzheimer's Disease. She found that:

Appearance, loss of self, and loss of the ability to recognize others were directly applied to people living with Alzheimer’s Disease

The epidemic threat, the fear and terror of those uninfected, and the idea of death as preferable to existence were referenced by way of implication to Alzheimer’s Disease generally.

Cannibalism applied to both patients with the disease and the effect that the disease has on others.

Are Monster Metaphors ‘Good’ or ‘Bad’?

Some scholars suggest that metaphors help us to understand something that we might not otherwise comprehend by imposing familiar frameworks on to an unknown or complex topic. For example, it may be easy for someone to understand how the spread of a virus occurs if we think about it in the context of zombie films and how quickly zombie viruses spread.

Metaphors and metaphorical language can also help to alleviate our fears and provide an explanation for something that might otherwise be inexplicable or horrifying. Understanding why a serial killer commits murder could be easy and comforting if we merely chalk it up to them being a monster - it also alleviates our fears because how many monsters can there be out there.

But, Susan Sontag, a renowned American writer, filmmaker, philosopher, teacher, and political activist, has written extensively about the problem of using metaphors in the context of disease, illness and disability. She suggests that using metaphors in disease narratives can impose meaning on to disease and deform the experience of people who are actually living with it. It's also not uncommon for such metaphors to result in victim blaming and shaming.

Sontag also says that metaphors create fear - fear of infection, fear of contamination - which results in the segregation of those who are sick or infected from those who are not. And, if we start thinking about people as less than or no longer human, what kind of implications does that have for death and dying with dignity?